James Clear: How Innovative Ideas Arise

In 2010, Thomas Thwaites decided he wanted to build a toaster from scratch. He walked into a shop, purchased the cheapest toaster he could find, and promptly went home and broke it down piece by piece.

Thwaites had assumed the toaster would be a relatively simple machine. By the time he was finished deconstructing it, however, there were more than 400 components laid out on his floor. The toaster contained over 100 different materials with three of the primary ones being plastic, nickel, and steel.

He decided to create the steel components first. After discovering that iron ore was required to make steel, Thwaites called up an iron mine in his region and asked if they would let him use some for the project.

Surprisingly, they agreed.

The Toaster Project

The victory was short-lived.

When it came time to create the plastic case for his toaster, Thwaites realized he would need crude oil to make the plastic. This time, he called up BP and asked if they would fly him out to an oil rig and lend him some oil for the project. They immediately refused. It seems oil companies aren’t nearly as generous as iron mines.

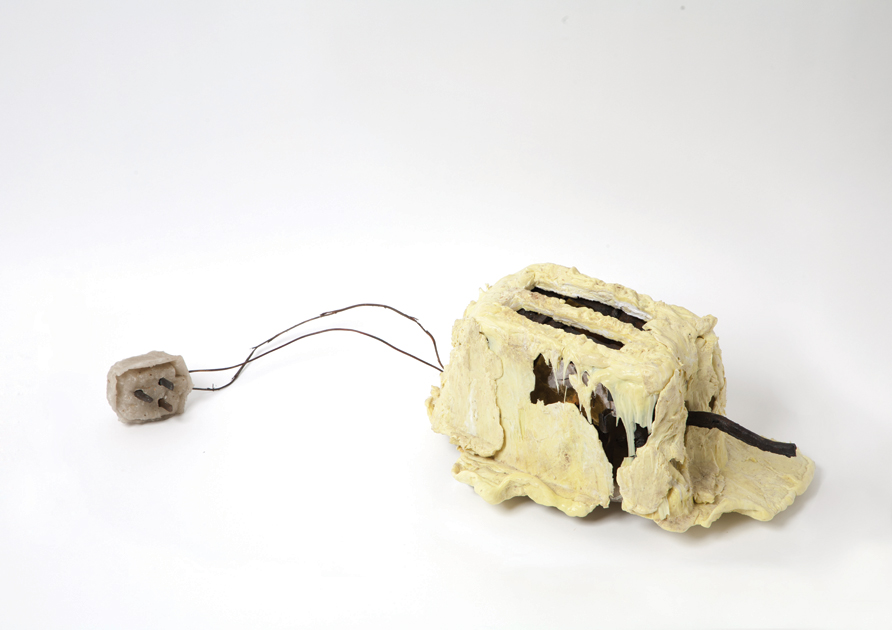

Thwaites had to settle for collecting plastic scraps and melting them into the shape of his toaster case. This is not as easy as it sounds. The homemade toaster ended up looking more like a melted cake than a kitchen appliance.

This pattern continued for the entire span of The Toaster Project. It was nearly impossible to move forward without the help of some previous process. To create the nickel components, for example, he had to resort to melting old coins. He would later say, “I realized that if you started absolutely from scratch you could easily spend your life making a toaster.”

Thomas Thwaites set out to build a toaster from scratch. The Toaster Project, as it came to be known, ended up looking more like a melted cake. (Photo Credit: Daniel Alexander.)

Thomas Thwaites set out to build a toaster from scratch. The Toaster Project, as it came to be known, ended up looking more like a melted cake. (Photo Credit: Daniel Alexander.)

Don’t Start From Scratch

Starting from scratch is usually a bad idea.

Too often, we assume innovative ideas and meaningful changes require a blank slate. When business projects fail, we say things like, “Let’s go back to the drawing board.” When we consider the habits we would like to change, we think, “I just need a fresh start.” However, creative progress is rarely the result of throwing out all previous ideas and completely re-imagining of the world.

Consider an example from nature:

Some experts believe the feathers of birds evolved from reptilian scales. Through the forces of evolution, scales gradually became small feathers, which were used for warmth and insulation at first. Eventually, these small fluffs developed into larger feathers capable of flight.

There wasn’t a magical moment when the animal kingdom said, “Let’s start from scratch and create an animal that can fly.” The development of flying birds was a gradual process of iterating and expanding upon ideas that already worked.

The process of human flight followed a similar path. We typically credit Orville and Wilbur Wright as the inventors of modern flight. However, we seldom discuss the aviation pioneers who preceded them like Otto Lilienthal, Samuel Langley, and Octave Chanute. The Wright brothers learned from and built upon the work of these people during their quest to create the world’s first flying machine.

The most creative innovations are often new combinations of old ideas. Innovative thinkers don’t create, they connect. Furthermore, the most effective way to make progress is usually by making 1 percent improvements to what already works rather than breaking down the whole system and starting over.

Iterate, Don’t Originate

The Toaster Project is an example of how we often fail to notice the complexity of our modern world. When you buy a toaster, you don’t think about everything that has to happen before it appears in the store. You aren’t aware of the iron being carved out of the mountain or the oil being drawn up from the earth.

We are mostly blind to the remarkable interconnectedness of things. This is important to understand because in a complex world it is hard to see which forces are working for you as well as which forces are working against you. Similar to buying a toaster, we tend to focus on the final product and fail to recognize the many processes leading up to it.

When you are dealing with a complex problem, it is usually better to build upon what already works. Any idea that is currently working has passed a lot of tests. Old ideas are a secret weapon because they have already managed to survive in a complex world.

Iterate, don’t originate.

James Clear writes at JamesClear.com, where he shares self-improvement tips based on proven scientific research. You can read his best articles or join his free newsletter to learn how to build habits that stick.

This article was originally published on JamesClear.com.

- Information for this story was collected from Thomas Thwaites’ personal website, The Toaster Project, and from his TED Talk titled, “How I built a toaster from scratch.”

- If you’re curious, I believe the closest living reptile ancestor to birds is the crocodile. You sort of imagine how reptile scales interlink and lay over one another in a similar fashion as bird feathers.

- I first read about The Toaster Project in Adapt by Tim Harford. He also discusses the interconnectedness of our modern world. It’s a good read if you’re interested in the idea of applying the concept of evolution to business and life. I recommend it.